A Do-It-Yourself Approach to Happiness

This is the second in a 9 part series on learning to practise Buddhism.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Words like “love” or “happiness” can mean a lot of different things to different people, or can mean different things when used in different circumstances. At the superficial end of the scale there is an advertisement for a popular ice cream at the moment which asserts “such and such ice cream will make us happy”. We kind of get what they are saying but in the context of Buddhism what are we referring to when we talk about our wellbeing and happiness?

We are not really talking about the happiness that comes when we experience something we like or acquire something we wanted.

That form of happiness from a Buddhist point of view is not very reliable or stable because as soon as we loose the thing we were happy about or as soon as the experience we like stops happening our happiness can shrivel up.

The pleasure of hearing a great new song fades off, our new clothes become old fashioned, your new car becomes outdated, our cutting-edge computer is soon too slow, and maybe even a past friend becomes a new enemy. The person we once loved now seems to irritate us.

These scenarios we all know too well. Getting what we want doesn’t make us really happy. Maybe it looks like it will make us happy at the time, but from a Buddhist viewpoint it is transitory and unreliable. Sooner or later everything wears out.

Also this type of happiness that depends on something outside us often has too much dependency and attachment in it.

This dependency tends to work against our happiness. For example, we may experience some happiness with our partner yet at the same time, because of our attachment to them we may experience such things as jealousy, possessiveness, insecurity and resentment because they won’t be what we want them to be.

We are focused too much externally. We see external improvement as our main investment for our wellbeing and our family’s wellbeing. Consider all the things we believe we need to improve. Home improvement, wealth improvement, car improvement, status improvement, job improvement, relationship improvement and so many things. How much of our perception and mental space is caught up in this belief that improving our external situation is all that is needed to be happy?

Do we really get to be happier over our lifetime as we attain these things? In any case can we be sure which of these things will last for us?

It’s not that these things are of no value. They are certainly important and necessary and we must attend to them. However, in essence, these things are just our mechanics for living. They are our supply chain of what is needed to support our life such as our food, our shelter, our clothing, our transport, our health, our education, and so on. But we can easily believe they are ends in themselves. We hope that this life support system when developed to a certain level will provide real security and happiness for us.

If our existing view of how happiness is produced did work we would be getting happier over time and we would see many others who have treaded this path being really happy all the time. Is this what is happening?

It becomes evident if you do the analysis that our happiness will never have a secure base if it is tied to external events and conditions which are outside our control. In contrast, the Buddhist approach comes from the understanding that to develop real happiness in our mind we need to focus on improving our mind and the way we experience living.

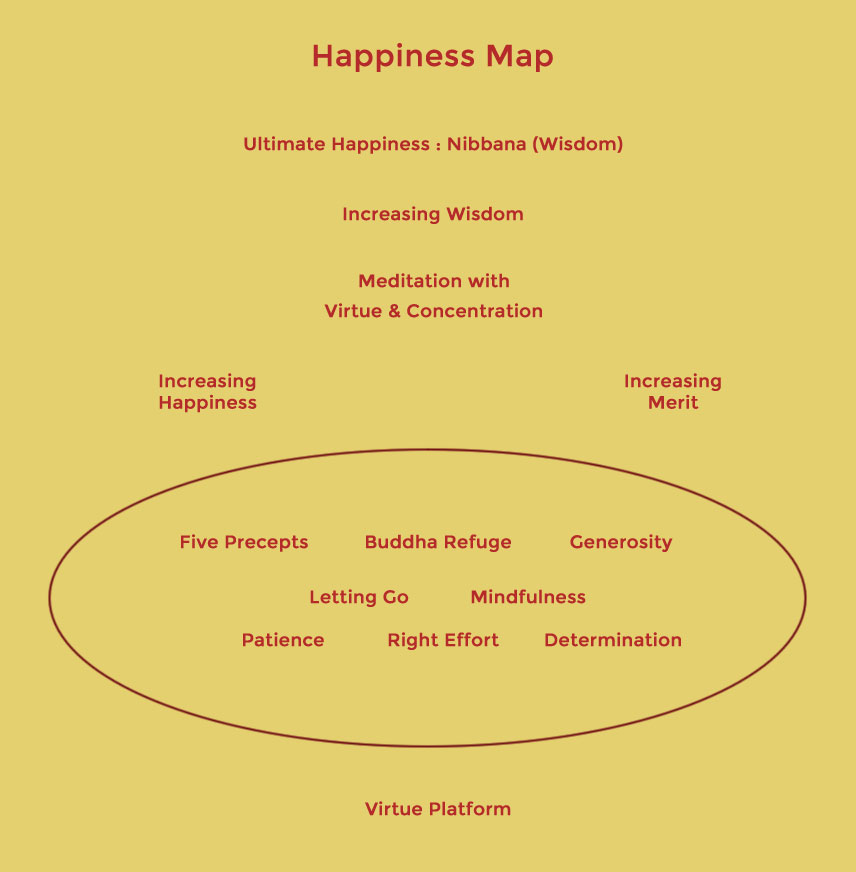

If we pick up a book on Buddhism we won’t find in it such a thing as a Happiness Map. However this map is a way of expressing the foundations or platform upon which a happy life can be created.

Buddhists who have done a bit of correct practice know this. Mental states such as worry, regret, stinginess, ill will, doubt, laziness, dullness of mind, greed, restlessness, attachment, conceit, aversion, boredom, jealousy and envy are all producers of unhappiness now and in the future. If we harbour these mental states they are drivers of unhappiness now, and because of the law of kamma they make causes for similar mental states to come back to us again in the future.

Together they make an unhappiness producing platform, or a stress producing platform, or a confusion producing platform.

As the Buddha says in the Dhammapada, Chapter 1:

“Mind precedes all mental states. Mind is their chief: they are all mind-wrought. If with an impure mind a person speaks or acts, suffering follows him like the wheel that follows the foot of an ox.” (Buddharakita) 1

We gradually train ourselves through Buddhist Practice to stop the negative or unwholesome minds from arising – now, and in the future. We apply restraint to our negative behaviour in the present and also apply the correct antidote behaviour in the present.

For example the Buddhist meditation to develop loving kindness called ‘metta’ meditation is one example of how we can prompt and cultivate positive wholesome consciousness and behaviour. The wholesome consciousness of metta or loving-kindness is everybody’s minds natural antidote to resentment, aversion, jealously and hate. As our love strengthens the negative states become progressively weaker and easier to give up.

This is the function of the “Letting Go” part of our Happiness Map. We give up and let go our unwholesome habits and behaviours. Gradually through practice we can recognise our negative states at both the gross and subtle levels, then we can let go of them instead of maintaining and strengthening them through our negative behaviour.

We don’t have to stay annoyed with someone who did something we didn’t like. When you see yourself starting to get stuck in any unwholesome thinking tell yourself to let it go. You actually say that as an instruction for your mind to follow. Tell the unwholesome state to stop. It’s not actually you, it’s not a “self” or something precious or important; it’s just one possible state that can arise for a period of time. Because it produces unhappiness and clouds your view give it up.

We can get quite good at dropping the unwholesome minds if you act quickly – cut them as soon as you first see them, before they become established in your mind. Learn to apply the correct natural antidote.

The second part of the Dhammapada quote reads:

“Mind precedes all mental states. Mind is their chief: they are all mind-wrought. If with a pure mind a person speaks or acts, happiness follows him like his never-departing shadow.” 2

We train our minds to produce the wholesome mental states such as confidence, mindfulness, friendliness, generosity, alertness, forgiveness, patience, fear of unwholesomeness, joy, equanimity, lightness of mind, adaptability of mind and loving kindness. According to the Buddhist texts there are 25 possible wholesome states of consciousness we can develop (See Appendix).

The reason that is a secure base for our happiness is because it is robust, it is resilient, it can bend with the wind rather than stress and break, it is intelligent and calm, it is built on inner strengths which can deal with the difficulties of life much better.

Over time through practice as our virtue platform becomes stronger our ability to handle misfortune without becoming upset increases.

We decide to be a kinder person, we decide to relate with others we know and meet with generosity and lightness of heart. We choose to become friendlier, offer others more warmth, more love and we consider others needs and offer our help when it would be beneficial. We start to view other people we know as our guests.

Training our mind to be wholesome is the way a true platform for our happiness in this life is built. According to Buddhism, the wholesome minds and actions built in this life become powerful causes to have good rebirths in our future lives.

So the bottom line for all Buddhist practice is – developing wholesome minds and actions is a true foundation of our long term well being and happiness.

We are all going to get old age, sickness and death this life – that’s our body’s inescapable future destination. However, it is possible to maintain our wholesome minds as we get older, it is possible to maintain bright, intelligent, happy minds even as our body wears out. It is very common for people’s minds deteriorate along with their body’s deterioration as they get older but essentially it is because their minds are not trained to be wholesome.

Let us briefly look at a few other components of our Happiness Map.

From Buddhist understanding and experience when morality has been strongly practiced and developed it becomes a very clear and powerful level of mind.

In Buddhism there are no commandments or similar authoritarian rules of behaviour. This is because at the very heart of Buddhism is the principle that the individual is solely responsible for his or her own welfare, happiness or unhappiness, which arise just as a result of the persons own actions.

Buddhist morality does not accept that our life and wellbeing are the outcome of the will of a supreme or higher being. The basis of a person choosing to maintain moral behaviour, therefore, is not because it’s a commandment of the religion but because there is a clear understanding and comprehension that morality is our first and best defence against creating more suffering for ourselves in the future.

The Buddha advises us to train our minds and actions so that we keep five precepts.

The five precepts are:

To not kill living beings

To not steal

To not commit sexual misconduct

To not lie

To not take intoxicants that cloud the mind

The reason why the five particular negative actions that the precepts stop us from committing are highlighted is that the Buddha recognised that some negative actions are more powerful than others. They are more powerful in the sense that they produce more powerful kammic results.

He identified that the five negative actions of killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct and taking intoxicants produce the most potent negative kamma or most concentrated negative kamma for ourselves to inherit in our future.

Buddhism teaches that in ultimate reality most of the suffering we had experienced in our life came from us breaking the five precepts in past times.

If we take time to consider and reflect on this it is obvious many of the problems that afflict people and society at large arise from individuals not keeping these five precepts.

Buddhists see keeping precepts as Occupation Health and Safety for our life. These precepts are just like that – they are the minimum standards of safe action of our body, speech and mind so we do not come to danger in this life or future lives. Precepts are our most powerful form of personal protection as from the ultimate reality viewpoint they keep us safe and healthy.

This is a part of a platform or foundation of peaceful, content, happy minds and wholesome mental states. The practice of morality produces powerful good kamma as it is the opposite of the five actions which produce the most powerful negative kamma.

This type of good kamma is experienced by the doer as pure, peaceful virtuous minds and peaceful living conditions which are both needed by us to develop on the Buddhist path. There is no such thing as a virtuous person who kills other beings, or steals from others.

It is also a foundation of coming to see things as they really are as the peace and purity that comes as a result of keeping precepts enables our mind to develop right concentration in meditation which is a prerequisite to developing wisdom.

Mindfulness is the only way to keep your precepts.

We do not become paranoid about the precepts. We have all broken precepts time and time again in our past, but we decide from now on we have the intention to keep them. We learn how to keep them well and we train ourselves to guard them whatever we are doing.

If we do break a precept we don’t react to that with guilt or regret. We just note “I have more training to do!” We re-affirm that we intend to keep that precept from now on.

We can only keep precepts really well by being mindful of what we are doing on the present. We come into the present- we stop thinking that we will keep the precepts at some future time. We look at our situation now. We focus on what we are doing with our body, we consider for a moment before we speak or act and we watch the thoughts that are arising.

In this way we can guard ourselves and take control of our actions, our speech and thoughts to not kill, to not lie, etc. It is in the present time that the kamma is being made. If we do not recognise what is happening in the present, we cannot change anything.

In Buddhism we talk about deep levels of happiness which can become our normal experience of living. These forms of happiness can more easily withstand the ups and downs of life which have in the past usually caused us to experience difficulty.

Buddhism says even this happiness can be surpassed by the nourishment of deep contentment and serenity and finally the sublime state of nirvana where the mind becomes unshakeable and never strays from perfect peace.

References

- Translated by Buddharakita. The Dhammapada. Published by Sukhi Hotu Sdn Bhd, Chapter 1, Malaysia, Yamaha Vada The twin verses.

- Translated by Buddharakita. The Dhammapada. Published by Sukhi Hotu Sdn Bhd, Chapter 1, Malaysia, Yamaha Vada The twin verses.

Appendix

The Buddhist Abhidhamma texts explain that there are fourteen different aspects of greed, hate and ignorance which manifest in our minds as specific mental components or mental cetiskas (Pali).

These different factors arise in conjunction with our different states of consciousness. They are referred to as unwholesome because they contribute to our unpleasant mental experiences and if acted upon contribute to making kamma which will fruit as some form of suffering.

The fourteen unwholesome mental states (cetasikas) and the twenty-five wholesome mental states (cetasikas) are listed below.

We can relate to these lists as being the mind equivalents of the periodic table of elements of matter as described from the scientific viewpoint.

Unwholesome Mental Components

1. Ignorance (moha)

2. Lack of moral shame (ahirika)

3. Lack of fear of unwholesomeness (anottappa)

4. Restlessness (uddhacca)

5. Attachment (lobha)

6. Wrong view (ditthi)

7. Conceit (mana)

8. Aversion (dosa)

9. Envy (issa)

10. Stinginess (macchariya)

11. Regret (kukkucca)

12. Sloth (thina)

13. Torpor (middha)

14. Doubt (vicikiccha)

Wholesome Mental Components

1. Confidence (saddha)

2. Mindfulness (sati)

3. Moral shame (hiri)

4. Fear of unwholesomeness (ottappa)

5. Disinteredness (alobha)

6. Amity (adosa)

7. Equanimity (tatramajjhattata)

8. Composure of mental states (kayapassadhi)

9. Composure of mind (citta kayapassadhi)

10. Lightness of mental states (kaya-lahuta)

11. Lightness of mind (citta-lahuta)

12. Pliancy of mental states (kaya-muduta)

13. Pliancy of mind (citta-muduta)

14. Adaptability of mental states (kaya-kammannata)

15. Adaptability of mind (citta-kammannata)

16. Proficiency of mental states (kaya-pagunnata)

17. Proficiency of mind (citta-pagunnata)

18. Rectitude of mental states (kaya-ujukata)

19. Rectitude of mind (citta-ujukata)

20. Right speech (samma vaca)

21. Right action (samma kammanta)

22. Right livelihood (samma ajiva)

23. Compassion (karuna)

24. Sympathetic joy (mudita)

25. Wisdom (panna)

It is very useful to have these lists to refer to as they are some of the real building blocks of our mental life. Using them as checklists helps us recognise these mental factors operating in our consciousness from moment to moment.

If we can accurately identify which cetasika is arising in our mind, we can decide what to do next; either cultivate them if they are beneficial or apply the correct antidote practice to reduce them if they are not beneficial.